Tuesday 26 July 2019

The how and why of The Swinburne Social Startup Studio

Before launching the Swinburne Social Startup Studio, we undertook a piece of foundational work aimed at consolidating what is already known, through research and experience, about early-stage social enterprise. To do this, we looked to the (surprisingly extensive for an emerging field) body of published research on social entrepreneurship and social enterprise development, which tends to span from the first decade of the 2000s until now.

We also endeavoured to capture the knowledge that exists in the deep experience of social enterprise practitioners; so we undertook research interviews with 11 social enterprise founders in an attempt to capture their insights on the critical aspects of early-stage social enterprise planning and execution.

What may be reassuring for some people to know is that there is strong consistency with the insights about social enterprise in the research literature, and the themes that emerged from our research interviews with the founders of the 11 Australian social enterprises.

The key insights from this research have informed our starting point for the Swinburne Social Studio – both in terms of our overarching ‘Studio Principles’ and also the more specific aspects of ‘how’ we will work with early-stage social enterprises and ‘what’ our approach will include. We say ‘starting point’ because the Social Startup Studio is a ‘living lab’, in which we will continue to test and refine ways of supporting early-stage social enterprises as we work with them. Reflecting our commitment to public knowledge, we will share the results of this work freely, to strengthen the enabling environment that is part of a healthy social enterprise ecosystem (Bloom and Dees 2008).

So far, three main insights have emerged that are informing our approach …

Insight one: Forget unicorns, social enterprise is a Pegasus

The hybridity of social enterprise, as a model in which both commercial and social institutional logics are brought to bear, is well documented in the academic literature (for example see: Austin et al., 2012; Barraket and Collyer, 2010; Pache and Santos, 2010; Santos et al., 2015). Published research has identified that, in addition to the opportunities presented by bringing together commercial and social logics, hybridity results in tensions and challenges for social enterprises that commercial enterprises, operating under a singular logic, don’t experience. These challenges include:

- the market failure contexts that many social enterprises operate in;

- the complexity of measuring performance when the organisation’s mission extends beyond profitability to social impact generation;

- accessing traditional capital markets due to the impact of social purpose on profitability and/or the non-distributive nature of not-for-profit legal structures; and

- human resourcing to achieve the commercial and social impact objectives of the enterprise (Austin et al. 2012; Pache and Santos, 2010; Al Taji and Bengo, 2018).

In contrast to the much sought-after billion-dollar unicorns of private, commercial entrepreneurship (Lee, 2013), social enterprise lives in the land of the Pegasus. A land in which Darwinian-like forces have conferred an advantage on organisations that can simultaneously fly and canter.

The implications of the hybridity of the social enterprise model also emerged strongly in our discussions with social enterprise founders; they emphasised the importance of acknowledging the tensions created by the often competing financial and social impact logics as an important part of developing a new social enterprise:

” … just being able to understand that there’s going to be tension there. It’s going to be that tension between making money and profitability and impact, and just understanding – first you have to acknowledge it. … So, once you figure out that you’ve got to do those two things together, and there’s going to be tension, and then you try to slowly figure out where the tension has to sit.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Our interviews also supported the research literature about how some of these tensions manifest at the operational level, such as the complexity of stakeholder relationships in social enterprises:

“…you’ve got a particular level of extra complexity in a social enterprise because you’ve got multiple stakeholder accountability. You’ve got so many magnitudes, more human relationships because you’re dealing with your beneficiaries. But often they’re part of a broader service system that comes attached to them so you’re dealing with just such large volumes of relationships.”

Social Enterprise Founder

… And having the right human resources to deliver a hybrid model:

“… we are better to find very young graduates out of uni and grow our own social enterprise practitioners in a hybrid environment than often taking very highly experienced people who have been too enculturated in their industry.”

Social Enterprise Founder

… And accessing capital:

“…we’ve found that there is a gap here and there is a different approach that needs to be taken …And I’ve found there have been conversations where someone has looked at our finances and said ‘if there’s an investment going in here of this amount of money, I’d like to see, within 12 months, this kind of return’ I’m like so, financial return, yes, what about the social return? What’s that? Let’s take a step back now.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Hybridity also impacts on who social enterprises can turn to for help and advice:

“We’ve also had a lot of support offered where people are very good at being consultants… … if they don’t have the experience in social enterprise, we spend more time explaining ourselves and front loading than we do actually receiving any useful feedback and I’ve been in that situation quite a few times. … Because they’re drawing on business to offer that expert advice… it’s not expert advice at that point then is it. They’re expert in one field but their advice is not relevant.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Insight two: It takes a village

The research literature suggests that social enterprises often have many and diverse stakeholders, including those that provide financial and other forms of support (Austin et al., 2012).

“I think it’s a blend of partnerships and of people that have really helped us, I guess, get where we are today.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Most of the social enterprises we interviewed highlighted the importance of starting to build their community of support. And build it early. They emphasised the value of aggregating a group of people who deeply understand them and their enterprise to offer advice and help guide decision-making and development.

“The details are where everything happens because people will really kill you with kindness in this space, so having people who are in the details and who are willing to be critical and challenge is really great. I also think – like, from my perceptive, I’ve always, and I still do – I find it hard to identify where I actually need help, because I don’t have a really clear – like, in my mind, it’s not clear what the next steps are.”

Social Enterprise Founder

The comment above not only highlights the importance of a network of support but also the value of that those offering the support being ‘in the details’. This aligns with the concept of ‘situated learning’ (Suchman 1987) and specifically ‘communities of practice’, in which new ways of doing things come about through people participating together in problem-solving in a practice-based context (Jarzabkowski, 2004). This is perhaps particularly necessary in an emerging, hybrid field like social enterprise, in which standard ‘ways of doing things’ from either the commercial or social/welfare worlds may not necessarily work and therefore adaptive practice is required.

Several of the social enterprise founders spoke of the importance of the early-stage support being situated and ‘applied’ to their specific social enterprise.

“It was about us, and it wasn’t – we were learning through ourselves rather than learning generic finance or budget concerns. So, it was all applied to us, which I think meant that it was critical, relevant and easy to digest. Because, yeah, finance and numbers are definitely not my strength, but once they came out of the theoretical into the practical and were applied, that was really important.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Another aspect of the supportive, practice-based community, which the social enterprise founders identified as important to their development was the importance and value of ‘critical friends’. As one social enterprise founder stated:

“But I think having that person that can be really honest with you, and just go, ‘Well, the reality of this is this is what it looks like. Now if that’s what you want to go out and do, do that, and contribute in that way. But this is where the challenges are.”

Social Enterprise Founder

And sometimes, it is important to have people who can have the difficult conversations…

“So there are a lot of people out there with amazing aspirations. How do we support those people and separate the people who have actually got something that has potential, from the people – from the dreamers. So being really a critical friend, I guess, or a critical filter for – and bursting people’s bubble early, so to speak. So they don’t continue and spend a whole lot of energy, only to come to a problematic place down the track.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Included in this ‘community of practice’ are funders. In contrast to commercial entrepreneurship, in which founders often provide the initial capital in the hope of eventual ‘harvest’ of the enterprise, there was a suggestion from the social enterprise founders we interviewed that there is value in early engagement with potential funders, inviting them to be part of their community of practice:

“… just bringing funders on that journey I found was really important and if I could wind back the clock I probably would have been talking to more funders in the early stage for them to see the journey. Because the journey is really impressive and I like that story, but we were trying to get a lot of things right before we tried funders. But I actually just think funders are just people and can be very curious and they can come on the journey as well.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Insight three: The road is long, with many a winding turn (apologies to The Hollies)

There is very little in the research literature about the time it takes for new social enterprises to get to the point of impact generation and financial sustainability. Our interviews with social enterprise founders indicated a range of one to three years of pre-trade planning and piloting, and anywhere between three and five years until a sustainable business model emerges in practice. This timeframe is highly dependent on the business model and social purpose. Whilst our interviews show some variability in the time to get to financially sustainable impact, our sample suggests that social enterprise startup is generally not a rapid process:

“The thing that I am so relieved that we did was take the time at the front end to research and think. And when I say take the time it was the best part of two years. And it wasn’t like I was sitting for two years solidly doing nothing but that. I gave up my day job and I committed to building the organisation, and it took more than two years to starting the organisation.”

Social Enterprise Founder

And…

“We’re in that year seven, coming into year seven. It’s probably just coming out of start-up at the moment. The last three or so years have solidified a little bit more, and we’ve had a major strategy review in the last 12 months…So, it would be that – we’ve got across – we’ve got across our chasm, but we’re sort of now on the other side of that and now…”

Social Enterprise Founder

Many of the social enterprise founders also suggested that developing a social enterprise is not a linear process:

“… we’ve explored lots of different models … and, what’s right? … And I think we’re always, I guess we’re always navigating our way around that, and I guess a really difficult question to ask ourselves – and I guess we’ve been through a number of iterations with that.”

Social Enterprise Founder

Acknowledging the iterative nature of early-stage social enterprise development aligns with the concept of ‘strategy as practice’ – the idea that an organisation’s strategy is an ongoing process of reflection and adaptation; that strategy is something that an organisation does not has (Cook and Brown, 1998). It is also reflective of the need for greater levels of adaptive practice in new and hybrid contexts (Jarzabkowski, 2004).

There is some evidence in small and new businesses that strategic planning is most effective when it is a dynamic process of planning, doing, learning and re-planning (Brinckmann et al. 2010).

The need for a dynamic and adaptive approach to early-stage social enterprise development emerged as a strong theme in our discussions with social enterprise founders:

“So, having that flexibility. I think just testing and learning was critical from the beginning. So, in terms of process I think you can sit around conceptualising and writing business plans and looking for funding, et cetera, but until an idea is actually real, I think that was really critical in that we didn’t sit around waiting for that; we had ideas and we just started testing and we weren’t afraid of the risks.”

Social Enterprise Founder

They describe the importance of being reflective, adaptive and constantly allowing that to inform their decision-making:

“We’re a reflective organisation and that’s connected. It comes from our strategy and it comes from our values. Because we have structured approaches to reflecting on events, reflecting on situations and scenarios and then our response is kind of connected to that…”

Social Enterprise Founder

There is also some suggestion that the dichotomy between planning and doing is a false one:

“…and I think that goes right back to, not just the business planning, but the strategy works that we’ve been doing over the, basically since we started…Whereas we could have easily got on with a more of a cookie cutter approach …I don’t know how else to put it other than being strategic, so creating strategies that have multiple avenues in them, models and different scenarios that we have identified approaches to. And that’s just storytelling, as well. That’s just a choose your own adventure story. But then at the same time having a set of principles and values that are actually embedded within the organisation not just written in the business plan that’s filed away in the drawer. We’ve done a lot of work in embedding that and in keeping ourselves true to it. And that flows through in so many different ways…”

Social Enterprise Founder

So, what does this mean for social enterprise startup?

Despite the hybrid nature of social enterprise, generally, support for early-stage social enterprises has mirrored that of the commercial world in process and format. Guillermo Casasnovas from Oxford University and Alberto Bruno from Santa Clara University undertook a review of 40 support programs for social ventures, which they classified as either ‘social incubators’ or ‘social accelerators’, noting that both terms are borrowed from the commercial entrepreneurship world (Casasnovas and Bruno, 2013). Most of the accelerators/incubators they studied have a fixed timeframe, with the majority running for between 2 and 12 months and offering a specific program of support.

Whilst to some extent standardised programming and defined timeframes are a reality of the cost of providing support to early-stage enterprises (be they social or commercial) our research suggests that this approach may not be the most ideal response to the issues presented by hybridity and the unique world of social enterprise startup – the need to build a community of practice (rather than focus on the founder/s alone) and the long and adaptive path of social enterprise development.

In short, I guess we are asking, given that there is strong evidence that social enterprise exists in a hybrid world, which means it presents different opportunities and experiences different challenges to commercial businesses, are approaches largely borrowed from that world – concepts such as ‘acceleration’ and ‘incubation’ applicable? Perhaps early-stage social enterprise development is more like a process of steady percolation in which the emerging social enterprise bubbles away, iterating and adapting until the desired brew strength is attained?

But how does percolation become a process?

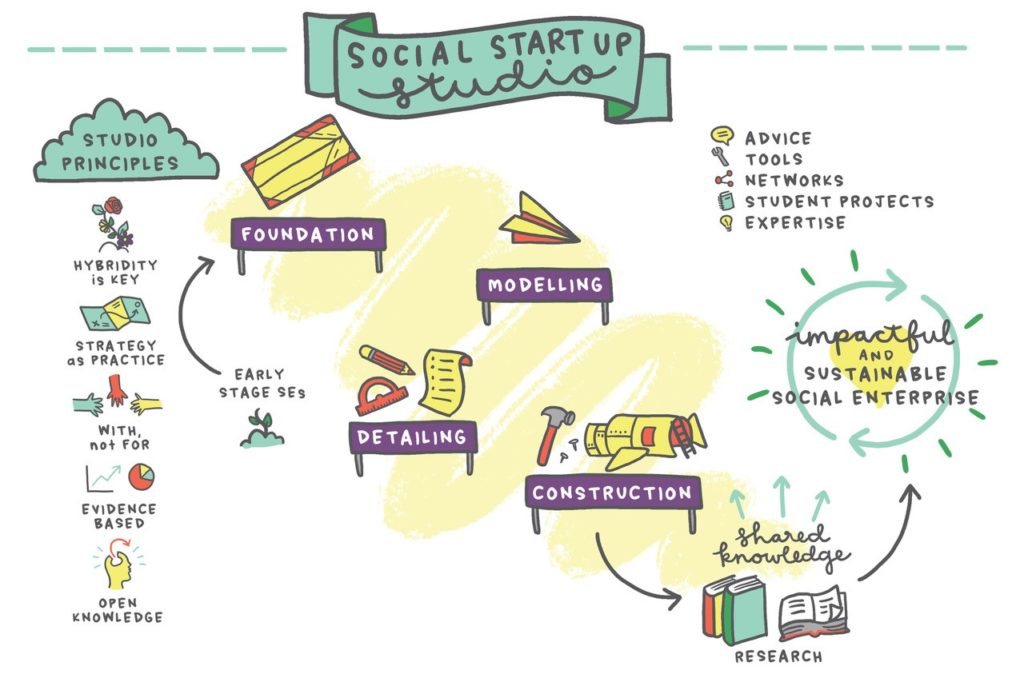

We are thinking that perhaps social enterprise development is more akin to a quest than a process; non-linear, creative, adaptive, context-specific and leveraging the environment to arrive at their goal – impactful and sustainable operations.

The path in the illustration below is our initial synthesis of our experience and research, which we will test and refine through the Social Startup Studio. We have notionally identified five Studio Principles and four development stages in the social enterprise startup quest: foundation; modelling; detailing; and construction. Within each of these stages, there are a number of ‘elements’ (see our website for these elements) that most enterprises require to move to the next development stage. These elements are not necessarily acquired on the first try and not in a prescribed order.

Our job is to guide and support early-stage social enterprises in their quest, according to the Studio Principles to adapt and refine our approach as we go and to share what we learn with the broader social enterprise ecosystem.

For more information on the Swinburne Social Startup Studio go to http://www.socialstartupstudio.com.au/

The Swinburne Social Startup Studio is an initiative of the Centre for Social Impact Swinburne, Swinburne University of Technology. The Social Startup Studio would like to acknowledge and thank Equity Trustees for their financial support, which has been provided by the following trusts in Equity Trustee’s SIP program: Alfred Edments Trust, Truby & Florence Williams Charitable Trust, Harold Moreland Oldham Perpetual Trust, VCF – ANZ fund, VCF – Clare Susan Gardiner Trust, Victorian Community Foundation – General Bequests, CH & CE Waddell Trust, managed by Equity Trustees.

References

- Al Taji, F.N.A., Bengo, I., 2018. ‘The Distinctive Managerial Challenges of Hybrid Organizations: Which Skills are Required?’ Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1–18.

- Austin, J. Stevenson, H. and Wei-Skillern, J., 2012. ‘Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both?’ Revista de Administração 47 (3): 370–84.

- Barraket, J. and Collyer, N. (2010) ‘Mapping Social Enterprise in Australia: Conceptual debates and their operational implications’. Third Sector Review 16 (2): 11–28

- Bloom, P. N. and Dees, G., 2008. ‘Cultivate your ecosystem’. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 6(1), 47-53.

- Brinckmann, J., Grichnik D. and Kapsa D. (2010) ‘Should Entrepreneurs Plan or Just Storm the Castle? A Meta-Analysis on Contextual Factors Impacting the Business Planning- Performance Relationship in Small Firms’. Journal of Business Venturing 25(1), 24–40

- Casasnovas, G. and Bruno, A. 2013. ‘Scaling Social Ventures: An Exploratory Study of Social Incubators and Accelerators.’ Journal of Management for Global Sustainability 1 (2): 173–97.

- Cook, S., and Brown, J., 1999. ‘Bridging epistemologies: The generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing’. Organization Science 10: 381– 400

- Jarzabkowski, P., 2004. ‘Strategy as Practice: Recursiveness, Adaptation, and Practices-in- Use’. Organization Studies 25, 29–560

- Lee, A., 2013. ‘Welcome To The Unicorn Club: Learning From Billion-Dollar

- Startups’. TechCrunch. AOL accessed via https://techcrunch.com/2013/11/02/welcome- to-the-unicorn-club/ on 8th July 2019

- Pache, A.-C., Santos, F.M., 2010. ‘Inside the Hybrid Organization: An Organizational Level View of Responses to Conflicting Institutional Demands’. SSRN Journal pp.64.

- Santos, F., Pache, A.-C., Birkholz, C., 2015. ‘Making Hybrids Work: Aligning Business Models and Organizational Design for Social Enterprises’. California Management Review 57, 36–58.

- Suchman LA. (1987). ‘Plans and situated actions: The problem of human-machine communications’. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.